Introduction:

The following presentation investigates Singapore’s aging population in detail and delves into the main reasons why the population is so disproportionately dominated by older individuals. After careful research, it was determined that the main reason why Singapore’s population is aging rapidly is chiefly caused by the rapidly decreasing birth rate of the nation state. The following graphics in this investigation will discuss the relationship between the two and solutions the Singaporean government has attempted to employ to solve this pressing issue.

Singapore’s Old and Aging Population:

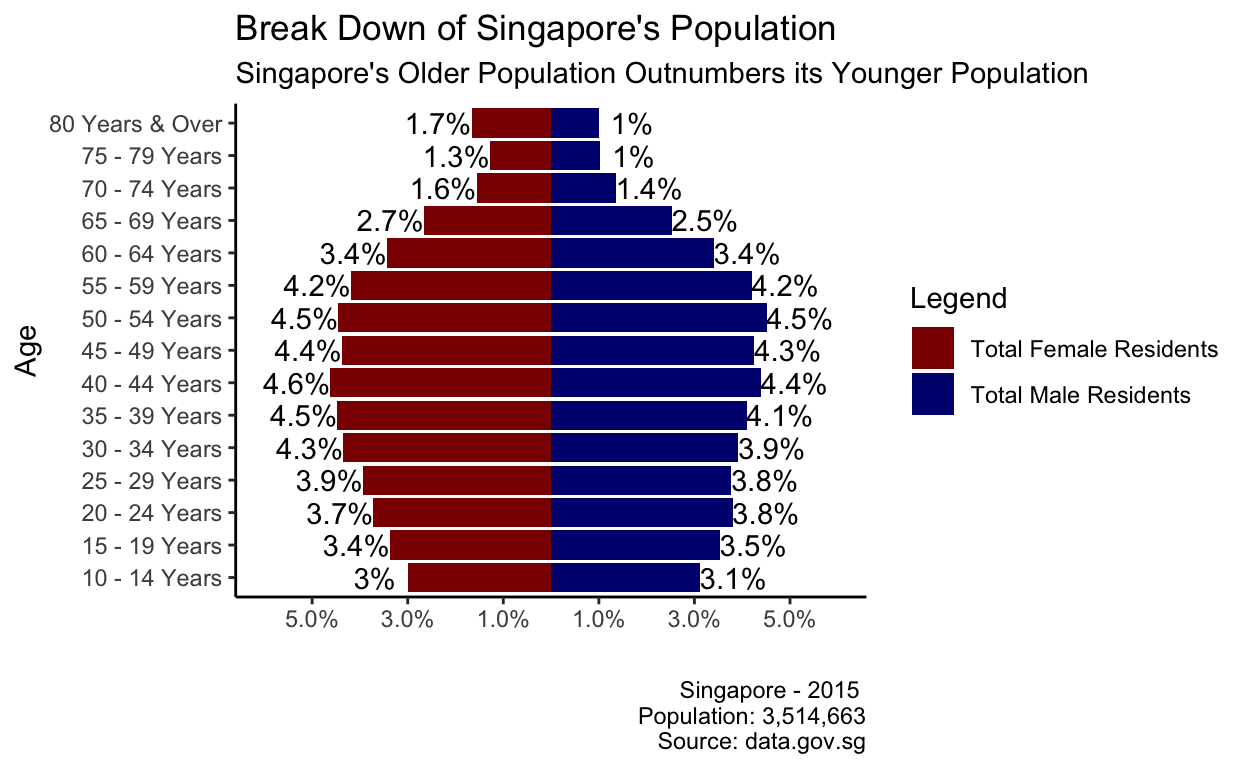

Below we have a graphic (population pyramid) depicting the makeup of Singapore’s Population in 2015. Every red bar represents the percent of women of that age group in the sample population and every blue bar represents the percent of men of that age group in the sample population. According the the graphic, Singapore’s - sample - population in 2015 was 3,514,663; men making up 48.9% population or approximately 1,718,670 in number. And women making up 51.1% of the population or approximately 1,795,993 in number. The y-axis shows that the age ranges of 10 - 80 & over were sampled. The data was retrieved from data.gov.sg.

According to the graphic above, 28.2% (approx. 991,135) of the individuals sampled in this graphic are 29 years or younger. Meaning that 71.8% (approx. 2,523,528) of the sample population is older than 30. This gives a little insight as to why Singapore’s population is getting older faster. A woman’s fertility peaks between the late teens and late-20s, after which it starts to decline slowly; fertility generally starts to reduce when a woman is in her early 30s, and more so after the age of 35. By age 40, the chance of getting pregnant in any monthly cycle is around 5%. Therefore, if the majority of in a population are older, less children will be born. Although the graphic only shows data for the year 2015, the disparity between the old and young in Singapore’s population has increased each year. This led me to conclude that one of the main causes of Singapore’s rapidly aging population is due to low and declining birth rates.

Why Does This Matter:

One might ask, “Why this is a big deal?” It is extremely common for developed or “first-world” countries to experience a dip in birth rate as a byproduct of economic progress. While this is true as a total fertility rate below the replacement level of 2.1 is now the norm for advanced economies. Singapore, along with many other east and south-east Asian countries have been experiencing extremely low birth rates through the years. Well below the global average. In the absence of immigration, Singapore is set to experience the most rapid population aging - as depicted in the graphic above - and decline.

Singapore’s Declining Birth Rates:

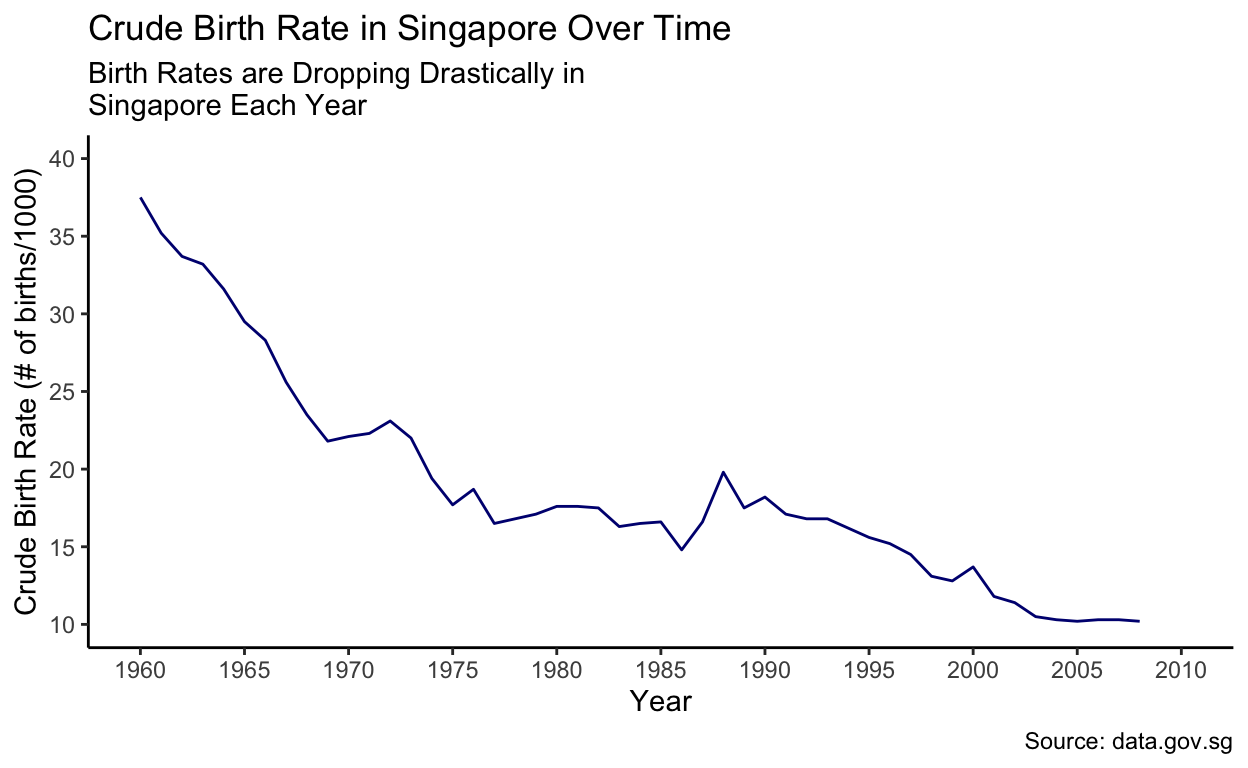

Below we have a graphic depicting Singapore’s crude birth rate over the years.

-Note: Crude birth rate is the number of live births per 1000 population in a given year.

The x-axis correlates with the year and the y-axis correlates to crude birth rates. The data was retrieved from data.gov.sg.

Singapore’s Declining Birth Rates (Cont.):

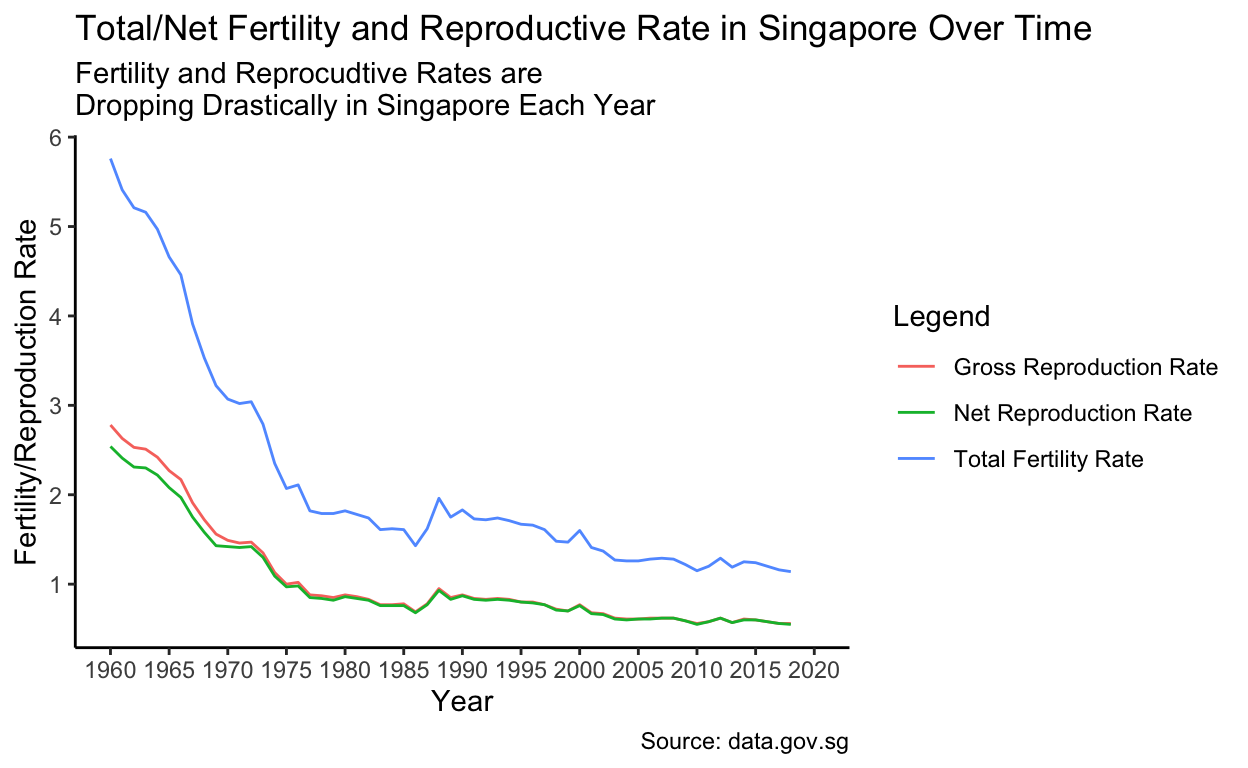

Below we have a graphic depicting Singapore’s total/net fertility and reproductive rates over the years.

-Note I: Gross reproduction rate is the average number of daughters that would be born to a woman during her lifetime if she passed through her child-bearing years conforming to the age specific fertility rates of a given year.

-Note II: Net reproductive rate is the average number of daughters that would be born to a woman if she passed through her life-time from birth to the end of her reproductive years conforming to the age-specific fertility and mortality rates of a given year.

-Note III: Total fertility rate is the average number of children that would be born to a woman by the time she ended childbearing if she were to pass through all her childbearing years conforming to the age-specific fertility rates of a given year.

The x-axis correlates with the year and the y-axis correlates to fertility/reproductive rates. The data was retrieved from data.gov.sg.

As shown in the graphs above, Singapore’s birth rates have dropped dramatically and continue to drop each year, which is the major contributing factor to the nation-state’s rapidly aging population. One thing that is quite interesting about this particular data is that the most drastic drop in birth/fertility/reproductive rates were between the years 1960 and 1975. Singapore gained independence in 1965 and began to rapidly progress economically during that time until around 1985 which was when they were finally considered a “first world country.”

Globally, the mean age of childbearing has increased by approximately one year a decade among Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OCED) countries, according to calculations by Oxford University’s Melinda Mills and colleagues (Mills and others 2011). In Singapore, changes in the age composition of women giving birth have been especially dramatic. Women ages 20–24 are now as likely to give birth as women ages 40–44 and far less likely than women ages 35–39. Moreover, unlike in a number of European countries, the steep decline in fertility among women in their 20s has not been offset by higher birth rates among women in their 30s.

Solutions:

The government has grappled with the relentless downward trend in fertility since the 1980s. After a public campaign and limited programs failed to produce results, a package of pronatalist incentives was introduced in 2001 and enhanced over the years. Currently, the package includes paid maternity leave, childcare subsidies, tax relief and rebates, one-time cash gifts, and grants for companies that implement flexible work arrangements. Despite these efforts, the fertility rate deteriorated from 1.41 in 2001 to a precarious 1.16 in 2018.

A new Singaporean policy approach aims to create a more conducive environment for marriage and fertility for all groups—in particular to help married women reconcile labor participation with motherhood. However, few if any of the instruments are designed specifically to allow women to become mothers at peak childbearing ages, either to stem the decline among women in their 20’s or to boost fertility rates among women in their early 30s. As a result, the lack of age sensitivity represents a lost opportunity to cater to the most receptive group of prospective parents.